Wholesome Places of Healing: Plantation Sickhouses and Medical Neglect

The abolition of slavery did little to alter the inherent violence of plantation labor regimes. The laws of the Barbados Abolition Act mandated men’s and women’s continued labor on the field for an additional four years as apprentices while simultaneously granting the freedom of all children under six years of age from 1834 to 1838.[1] Apprentices performed unrenumerated labor in exchange for housing, clothing, food, and medical care. The apprenticeship system organized former slaves into distinct categories with different dates to achieve full freedom. Children under six were freed immediately. The rest of the population was divided between two categories: praedials (agricultural laborer’s) who formed the majority of the population were to be freed in 1840, whereas non-praedials who performed work outside of the field/specialized labor were to be freed in 1838.

As a laboring mother of three, apprenticed to Warner’s estate, Hannah faced the difficult challenge of balancing the productive demands of the field with her reproductive carework. The brutal and unrelenting nature of post-slavery labor conditions pushed Hannah to a severe and debilitating illness.[2] For Hannah, emancipation, rather than being liberatory, was indexed by ongoing violence, medical neglect, and the inability to mother.

Unable to carry herself to the plantation hospital or “sickhouse,” Hannah’s mother pleaded to arrange for the estate manager Mr. Batson to have the district’s doctor pay a house call in light of her daughter’s debilitated condition. He refused and insisted that if Hannah desired medical care, it must be administered at the sick house. She promptly escalated her complaint to the special magistrate of District A, Captain Hutcheson. Hutcheson then forwarded a message to Batson requesting to accommodate Hannah. The manager refused to respond to Hutcheson’s request. Hearing the sound of the doctor’s horse pass her house, Hannah, in desperation, sent her young child to plead with the doctor to make a house call to treat her mother. Unmoved by her urgent appeals, the doctor declined to stop. Finally, Hutcheson resorted to sending two additional letters to the estate manager, insisting that he have the doctor visit Hannah at her mother’s home. By the time the doctor arrived, Hannah was in a critical condition, suffering from blisters and hemorrhaging. A few days later, Hannah died from a want of adequate medical care. She was survived by three young children, who were consequently dependent on their grandmother for support, who was “lame,” and reported herself “barely able to earn her own subsistence.”[3]

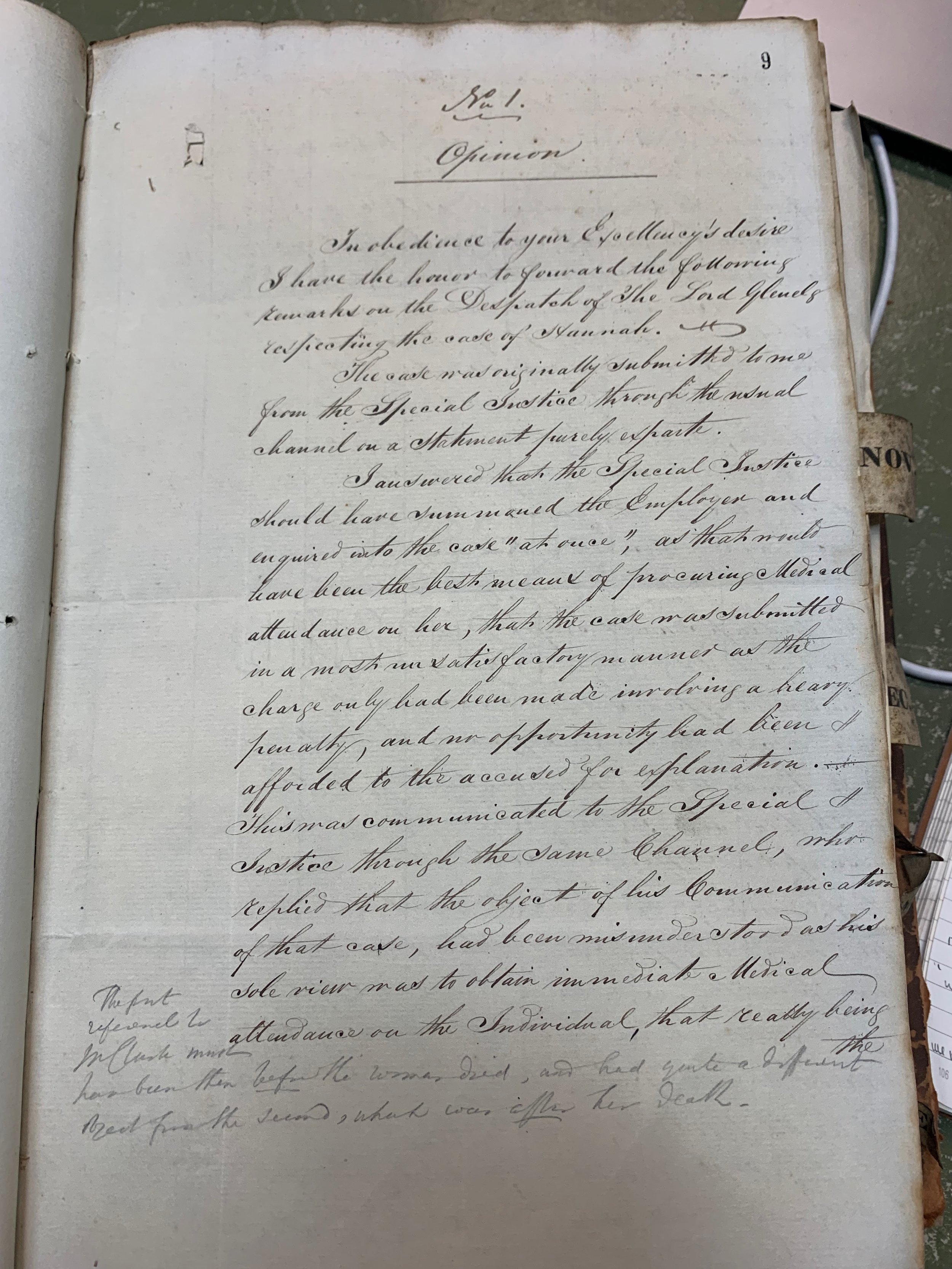

Hannah’s case prompted a criminal investigation into the circumstances of her death, which in turn produced an extensive archive. Across several pages of colonial correspondence records, we bear witness to planters’, doctors’, colonial and imperial state authorities’ competing visions of health and medicine. Moreover, and most importantly, this archive contains some of the earliest records of formerly enslaved peoples’ firsthand testimony about their experiences with post-slavery plantation medicine and their alternative visions of health and healing. The perspective of the apprentice is captured through magisterial reports. During the shift from slavery to freedom, the Colonial Office appointed magistrates to the West Indies as civil officers tasked with enforcing the Abolition Act and resolving minor disputes between laborers and planters. Throughout the apprenticeship period, magistrates maintained personal journals and sent periodic reports to the Crown, offering a firsthand account of the successes and failures of the apprenticeship system. Interwoven in the fabric of these documents are some of the key debates that would come to define the transition from slave to free-waged labor: 1) new capitalistic expressions of value about the black body, 2) emergent scientific and medical ideologies around the meaning of race, illness, and disability, and 3) the ongoing struggle toward bodily autonomy and black freedom.

CO 28/124, Oct 2, 1838, Special Magistrates Reports, The National Archives, London

CO 28/124, Oct 3, 1838, Special Magistrates Reports, The National Archives, London

The 34th Clause of the Abolition Act required planters to provide medical care to those apprenticed to their estate. Failure to do so could result in a £15 fine. However, Hannah’s death prompted Captain Hutcheson, the Governor, and the Attorney General to question what constituted adequate medical care. Who has the right to care, and who should be responsible for providing it? What measures should be used to identify what constitutes illness and debility? Hannah was not alone; her death signaled to Hutcheson “the inherent evils” embedded within the hospital rules and regulations, particularly the conditions of plantation sickhouses. Upon further investigation, Hutcheson discovered that colonists used plantation sick houses as secondary sites of punishment. In his diary, Hutchison described what he “found to be a dungeon, without even air or light when the door was closed and stocks fitted in it and probably used as a place of punishment in the ‘days of slavery.’”[4] He concluded that it was anything but a comfortable, sanitary and wholesome place of healing. Other apprentices issued complaints against their plantation managers for attempting to force them to undergo confinement in the sickhouse. If they refused, not only were they denied medical care, but apprentices fell under persistent accusations of “feigning illness” as planters attempted to push them back to work on the fields.[5]

Sites of healing became sites of terror. Planters leveraged hospitals and doctors to coerce the laboring population into the ceaseless production of sugar. Withholding care, quickly replaced the use of the lash as a new tool of punishment and labor extraction. In peeling through the layers of investigative records, it suggests how Hannah’s refusal to enter the sickhouse might go beyond her disablement. Her insistence in remaining in her own home, under the care of her mother, and surrounded by her children asserted her bodily autonomy. Hannah’s refusal to capitulate to the demands of her manager was a resistance to the coercive and violence tied to post-slavery plantation medicine. Hannah expressed an alternative vision of healing that prioritized women-centered communal care, comfort, and family support. She advocated for her right to medical care and the right to determine the terms under which she receives that care.

After several weeks of investigation, the Attorney General absolved Batson of any accusations of criminal intent or negligence in the case of Hannah’s untimely death. In accordance with the law, Batson agreed to pay the £15 penalty, half of which would go to the treasury, leaving the other half, Hutcheson stated, for the benefit of Hannah’s mother and three children. Colonial legal practitioners adjudicated that Hannah’s life amounted to £7.5.[6] Considering the Attorney General’s decision, it becomes evident that in slavery’s afterlife, colonial state actors found new ways to commodify, assign value, and generate profit from black death. In other words, the colonial state and its actors did not miss an opportunity to extract capital from black laborers, even in their death. The fine inflated the pockets of the treasury, not as restitution for the unquantifiable loss suffered by Hannah’s mother and her three unnamed children.

Through the new wave of black feminist scholarship on the reproductive politics of slavery, we are beginning to gain a much deeper understanding of the role medicine and early medical ideologies played in the interrelated processes of racialization and gender hierarchies.[7] However, we know much less about how medical violence shaped the possibilities and limits of freedom from the newly emancipated class. Gaining access to safe, sufficient, and affordable healthcare was a central struggle for freed people in post-emancipation societies. Elders and the infirm, like Hannah’s mother, faced widespread expulsions from plantations as their presence on estates was viewed as a financial burden because they could not pick cane. Meanwhile, children confronted a planter class that denied them access to care, including food, clothing provisions, and medical assistance, unless they legally contracted themselves to the estate as laborers.[8] The experiences of apprenticed laborers signal an ongoing struggle against medical racism and reproductive autonomy, which disproportionately affects black women and gender minorities today.

Halle-Mackenzie Ashby is a Ph.D. candidate in History at the Johns Hopkins University. She is the former African American History Mellon Scholars Dissertation Fellow at the Library Company of Philadelphia. Ashby is a historian of Caribbean slavery and emancipation, and her research concerns questions about gender, reproduction, and sexuality. Her dissertation, “Bound by the Womb: Reproduction, Kinship and Freedom in the Atlantic World” is an interdisciplinary history of how reproductive racial slavery gave birth to a post-emancipation carceral state that disproportionately oppressed black mothers.

[1] Melanie Newton, The Children of Africa in the Colonies: Free People of Color in Barbados in the Age of Emancipation. Antislavery, Abolition, and the Atlantic World. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008). 142

[2] CO 28/124, Oct 3, 1838, MacGregor to Glenelg, The National Archives (hereafter TNA), London

[3] CO 28/124, April 3, 1838, Special Magistrates Reports, District A, TNA, London

[4] CO 28/124, April 3, 1838, Special Magistrates Reports, District A, TNA, London

[5] CO 28/124, April 3, 1838, Special Magistrates Reports, District A, TNA, London

[6] CO 28/124, March 24, 1838, Special Magistrates Reports, TNA, London

[7] See Deirdre Cooper Owens, Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017, and Sasha Turner Contested Bodies: Pregnancy, Childrearing, and Slavery In Jamaica. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), 2017.

[8] CO 28/118, Nov, 1836, Copy of despatch MacGregor to Glenelg, Returns from the Special Magistrates, TNA, London.